© 2008 – 2019 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

In his review of the research, Stephen Norris notes that critical thinking in children is uncommon:

“Most students do not score well on tests that measure ability to recognize assumptions, evaluate arguments, and appraise inferences” (Norris 1985).

Why is critical thinking so difficult? Some argue that humans aren’t designed for it.

According to this idea, evolution hasn’t equipped us for abstract, logical reasoning. Instead, natural selection has shaped the brain to solve specific, evolutionarily- relevant, problems– like avoiding predators and identifying which people are breaking the rules (Tooby and Cosmides 1992).

Maybe these folks are right. I’m not going to argue that here. Instead, I want to make a different point:

We often train our kids to think in fallacious or illogical ways.

My evidence?

Consider these real-life examples of how TV, books, educational software, and even some teachers–discourage critical thinking in children.

How to discourage critical thinking in children: The case of Minnie Mouse

How about this a scene from Disney’s “Mickey Mouse Playhouse,” a TV program for preschoolers.

Minnie Mouse–Mickey’s feminissima pal–has a problem. She has been packaging and wrapping gifts, including a bow (just like the one on her head).

But Minnie forgot to label the packages she’s wrapped, and now she’s not sure which box contains the bow.

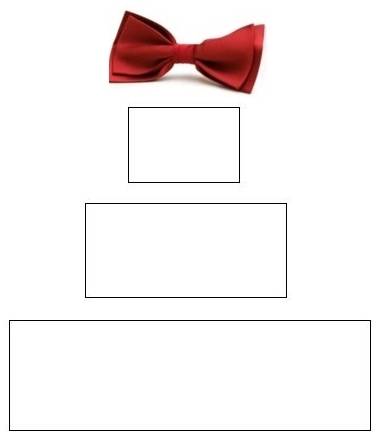

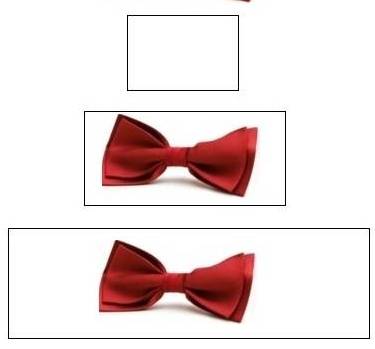

There are three possible boxes—small, medium-sized, and large.

Minnie asks: Which box might contain the bow?

Minnie holds out her hands to show us how big the bow is. She compares this with the size of the boxes. The bow seems too big for the smallest box. But it appears small enough to fit in the other two.

So…the answer is that the bow might be in either the medium-sized box or the big box. Right?

Wrong.

Minnie tells us that the bow MUST be in the medium-sized box.

Why does Minnie deny the logical possibility that the bow might be in the big box?

Presumably because the writers weren’t thinking straight and didn’t say what they meant.

Apparently, what they really wanted to ask was this:

“Which is the smallest box that the bow could fit in?”

But then again, there is the possibility that the bow could be in the smallest box. The bow seems too big for the smallest box. But what if Minnie had folded or wadded up the bow to make it fit?

So perhaps the writers should have posed this question:

“Which is the smallest box that the bow could fit in—assuming that Minnie didn’t scrunch up the bow?”

The point

Does this sound nit-picky or pedantic? Maybe it does to the writers of the Mickey Mouse show. But I’m really just asking for some common sense.

In the real world, people do scrunch and they really do sometimes package items in boxes that are a bit larger than needed. Why should we—the viewers—assume that they don’t?

The answer is that we shouldn’t. Not unless we know something about Minnie Mouse. Not unless we know what her unstated assumptions are.

And that’s the point. I don’t know what goes on in Minnie Mouse’s head, and I don’t suppose that my kids do, either. The writers of the Mickey Mouse show asked us to solve the problem based on information about the size of the bow and the size of the boxes.

Critical thinking means that we consider all the possibilities, not just the one that the Mouse thinks is most likely.

What happens when your child watches this sort of thing? It seems to me that the Mickey Mouse show is teaching something very different from critical thinking. It’s teaching kids conformist thinking. Don’t look at problems objectively or logically. Instead, figure out what the authorities want you to say.

You might wonder if young children really think this way. Aren’t kids — like the boy in the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes — supposed to speak their minds?

But experiments suggest that preschoolers are inhibited by the pronouncements of authoritative adults.

When grown-ups tell them how something works, kids don’t question it. They act as if the adults have told them everything they need to know. They become less inquisitive, less likely to investigate on their own (Bonawitz et al 2011; Buchsbaum et al 2011).

Not just Minnie Mouse: How formal educational experiences discourage critical thinking in children

It’s bad enough if children’s television programs are undermining critical thinking. But what about textbooks, educational software, and everyday experiences in the classroom?

I’ve found the Minnie Mouse fallacy in a book intended to teach math concepts to preschoolers. In this case, the reader was asked to find the right birdhouses for an assortment of (differently-sized) birds.

And of there are lots of other illogical or wrong-headed lessons that are kids are asked to absorb.

For instance, consider this story reported by educational psychologists Clements and Sarama (2000):

Young Leah is playing a computer game that teaches geometry. It asks Leah to choose a fish that is shaped like a square.

Leah picks a fish with a perfectly square body, but the shape is rotated so that one of its corners points straight down.

The program tells Leah that she’s wrong. That’s not a square. That’s a “diamond fish!”

Uh-oh. A square is only a square when two of its sides are aligned with the horizontal?

Teaching kids misconceptions about geometry

Clements and Sarama report other mistakes, including these misconceptions that kindergarten teachers have been observed to pass along to their impressionable young students:

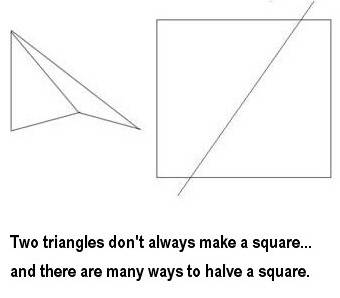

- All diamonds are squares

- A square is not a rectangle

- If you put two triangles together you’ll make a square

- If you cut a square in half you’ll make a triangle

And so on. You get the idea.

How much does this matter?

Clearly, we don’t want people teaching our kids things that are illogical and wrong. But how much damage does this really do?

Quite a bit, I’d say. In the case of Minnie Mouse, kids learn to think with blinders on. Don’t consider all the possibilities. Stick to the conventional solutions.

In the case of the square that isn’t really a square, kids learn bad facts and they lose the opportunity to build up a coherent theory of geometry.

The consequences may be long-lasting. Clements and Sarama report that 6-year olds may hold their misconceptions about geometry until they reach middle school.

What about Minnie? The kids who pass Minnie’s test are socially perceptive. They recognize their teachers’ implicit assumptions and tell their teachers what they want to hear. And they get rewarded for it until they meet up with a logical, less culture-bound teacher. Or a logical test. And then, perhaps for the first time ever, these kids start to fail.

What happens then? Do these kids conclude that they aren’t cut out for “hard core” courses in math or science? Maybe.

What can we do?

Experimental interventions suggest that we can teach critical thinking skills to middle school students, and maybe even younger kids.

For more information, check out these research-based tips for teaching critical thinking in children and adolescents.

As I note in that article, it appears that teaching critical thinking in children can actually boost their IQ scores.

And as for parents with very young kids–the kids who might be watching Mickey Mouse?

First up, we should take notice of a crucial discovery: Even before the age of 5, kids seem to understand that claims backed by evidence are more acceptable than claims lacking evidence.

They know, for instance, that it’s not enough for you to claim that you know what’s inside a container. If you haven’t looked, they’re more likely to judge your claim as unacceptable (Butler et al 2018; Fedra and Scmidt 2019).

So even young children are ready to talk about the fundamentals of fact-verification. How do you know? Did you look? Did you check?

But there is a complication.

As noted above, young children are also inclined to follow our lead.

This is a useful trait in a species that depends on transmitting cultural information. Kids are good imitators. But their eagerness to follow has a downside. In experiments, children exposed to adult instruction have become less inquisitive. They were less likely to test alternative ways of doing things.

For example, when an adult showed preschoolers a new toy, the children’s subsequent actions depended on how the adult behaved.

If the adult acted like a teacher — explaining the “correct” way to operate the toy — the children hewed very closely to the teacher’s procedure.

But if the adult acted clueless — as if she didn’t know how to operate the toy — the children tended to make a more thorough investigation of the toy’s features.

Kids were more likely to discover alternative ways of operating in the toy — including ways that were more efficient than the “correct” procedure modeled by the teacher (Bonawitz et al 2011; Buchsbaum et al 2011).

So if we want to nurture critical thinking, a good first step is to provide young children with opportunities to tinker and test and experiment — without telling them what to expect.

In addition, we should monitor the messages our children are getting — from people, books, electronic media — and discuss the errors we spot with our kids. We need to teach our kids that sometimes even smart, authoritative adults make mistakes.

And most of all, our kids need positive reinforcement for thinking critically, for being logical, and for offering unconventional solutions to problems. Before we correct a child’s wrong answer, we should reflect on whether or not it really is wrong.

References: Critical thinking in children

Bonawitz E, Shafto P, Gweon H, Goodman ND, Spelke E and Shultz L. 2011. The double-edged sword of pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery. Cognition 120(3): 322-330.

Buchsbaum B, Gopnik A, Griffiths TL, and Shafto P. 2011. Children’s imitation of causal action sequences is influenced by statistical and pedagogical evidence. Cognition 120(3): 331-340.

Butler LP, Schmidt MFH, Tavassolie NS, Gibbs HM. 2018. Children’s evaluation of verified and unverified claims. J Exp Child Psychol. 176:73-83.

Clements DH and Sarama J. 2000. Young children’s ideas about geometric shapes. Teaching Children Mathematics 6(8): 482-487.

Fedra E and Schmidt MFH. 2019. Older (but not younger) preschoolers reject incorrect knowledge claims. Br J Dev Psychol. 37(1):130-145.

Lucas CG, Bridgers S, Griffiths TL, Gopnik A. 2014. When children are better (or at least more open-minded) learners than adults: Developmental differences in learning the forms of causal relationships. Cognition 131 (2): 284

Norris SP. 1985. Synthesis of Research on Critical Thinking. Educational leadership 42(8): 40-45.

Tooby J and Cosmides L. 1992. Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. In: J Barkow, L Cosmides and J Tooby (eds): The adapted mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Content last modified 2/2019