Bedtime fading is a gentle, “no cry” technique for re-aligning your child’s internal clock with the bedtime you desire. You start by asking your child to go to bed late — late enough that your child experiences a powerful physiological urge to sleep. Then, over multiple days, you gradually adjust your child’s schedule, until your child is falling asleep at the earlier time you prefer.

Studies suggest that the fading approach is an effective way to overcome a child’s chronic resistance to going to bed. It’s also useful for getting a child ready for a new, earlier schedule.

But who is a good candidate for this sleep training method? What makes it different from other sleep training techniques? And what procedures should you follow to maximize success? This Parenting Science guide offers answers — and detailed instructions.

Who should try this technique?

Bedtime fading has been used on toddlers and older children. It’s been used on typically-developing kids, and on children with developmental disorders (Kang and Kim 2021). But it isn’t for every family.

To be successful, you need to invest some time in learning the concepts, analyzing your child’s current sleep habits, and troubleshooting. You also need to be ready to make some important changes.

For example, you’ll need to take steps to reprogram your child’s circadian rhythms. You’ll also need to change any environmental or lifestyle factors that are keeping your child alert at night. And you’ll have to be ready for some short-term difficulties, including setbacks, and daytime tiredness.

But if you’re willing to make the effort, you’re likely to see improvements. As I note at the end of this article, studies suggest that bedtime fading is helpful. Kids adapt to earlier bedtimes — falling asleep more easily and quickly.

Is bedtime fading a form of sleep training?

Does it have anything to with “cry-it-out” techniques? Or the Ferber Method? How is bedtime fading different? Bedtime fading can be considered a form of sleep training, but it’s very distinctive one.

First, it’s designed specifically for improving compliance at bedtime. It’s not focused on solving other sleep problems, like frequent night wakings.

Second, it doesn’t involve leaving children alone to cry. If that happens, you’re doing it wrong.

Third — and most importantly — bedtime fading is different because it addresses the physiological causes of bedtime resistance.

“Cry it out” techniques and the Ferber Method are designed merely to make children stay quiet during the night. They do not teach kids how to fall asleep, and they do nothing to ensure that a child will become physiologically drowsy at bedtime.

By contrast, bedtime fading is designed to change the brain’s internal clock. It gives children the biological tools they need to fall asleep promptly — without tears or protest.

So what are the crucial background concepts? What do parents need to know before beginning the procedure?

The bedtime fading technique was developed by two professors of pediatrics, Cathleen Piazza and Wayne Fisher, and it’s based on solid principles of sleep science and learning theory.

If you understand this background, the program’s steps will make sense to you, and you’ll be able to tailor the method to the specific needs of your child. Here are the key concepts.

1. To fall asleep, people must experience physiological drowsiness. So if a child isn’t falling asleep promptly at bedtime, this is a sign that the child isn’t drowsy enough. Something is getting in the way.

What’s causing the lack of drowsiness? As I explain elsewhere, kids fail to become sleepy for a variety of reasons. Here are some of the most common culprits:

- The child’s circadian rhythms are out-of-sync with the parent’s preferred bedtime. The child’s “internal clock” isn’t triggering the right brain chemistry as bedtime approaches, so the child isn’t physiologically capable of falling asleep.

- The child isn’t experiencing enough of what scientists call “sleep pressure,” i.e., too little time has passed since the child last slept, so he or she isn’t capable of feeling drowsy yet.

- The child suffers from nighttime anxieties or fear of the dark.

- The child is encountering too much psychological stimulation before bedtime; e.g., too much television.

- The child’s daily experiences have trained him or her to associate bedtime with conflict, stalling, and a failure to fall asleep. As bedtime approaches, the child anticipates trouble, and this anticipation blocks drowsiness.

This list isn’t complete, and it’s likely that your child is experiencing more than one of these problems.

Indeed, no matter what else is going on, it’s a good bet that your child is affected by the last problem on the list — learned, negative, bedtime associations.

The very fact that you’ve been trying to enforce a particular bedtime — trying and failing — suggests that all those nighttime struggles have turned into a kind of nightly routine for your child. Your child has developed a habit of bedtime sleeplessness.

But the key point is that something is actively preventing your child from feeling sufficiently drowsy and peaceful at bedtime. If you want your child to learn how to fall asleep easily and promptly, you need to eliminate these barriers.

2. Your child can make a breakthrough if you “reboot” your current routine.

You need to get rid of those negative bedtime associations and replace them with positive ones. You need to help your child learn that bedtime is a time of peacefulness, security, and powerful drowsiness.

Depending your child’s individual circumstances, this might mean eliminating a late afternoon nap; avoiding potentially disturbing or exciting television programs before bedtime; or addressing your child’s nighttime fears.

But whatever else you do, you should immediately stop trying to enforce your current, official bedtime. Instead, you should replace it with a later bedtime — a bedtime late enough that your child will experience powerful, physiological drowsiness.

This should make it easy for your child to fall asleep, promptly and without stalling tactics. And once your child has formed these new, positive sleep associations, you’ll be ready to move into the fading phase of training — the phase where you gradually move your child’s bedtime back to the earlier time you prefer.

3. After your child has experienced success with the new, later bedtime, you can use circadian cues — and incremental, nightly shifts — to adapt your child to the earlier bedtime you prefer.

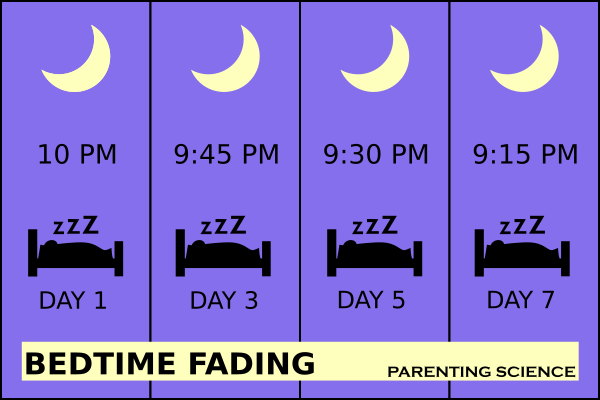

If you’ve ever had jet lag, you know how it works. You don’t instantly adjust to an earlier bedtime — not if the bedtime is substantially out-of-sync with our internal clock. But it’s pretty easy to get there if take a series of small steps. Expose yourself to bright light during the day. Avoid artificial light in the evening. And go to bed 15 minutes earlier each night.

So this is the approach that parents use in bedtime fading. The gradual pace is crucial, because you don’t want to re-establish those negative sleep associations. If, at any point along the way, your child has trouble falling asleep promptly (within 15 minutes of bedtime being announced), your child is at risk for re-learning that bedtime is difficult, unpleasant, or an occasion for stalling.

For this reason, Piazza and Fisher incorporate backward steps in their program. When a child doesn’t adjust to the latest incremental change — i.e., when the child fails to fall asleep promptly after you’ve rescheduled bedtime for 15 minutes earlier — you don’t keep pushing ahead. Instead, you immediately revert to the later bedtime.

How do you actually implement bedtime fading? Here’s a step-by-step guide, with examples.

1. Estimate your child’s sleep needs, and set a realistic goal for your child’s bedtime and morning wake-up time.

For help, review the recommended sleep times for individuals in your child’s age bracket. In addition, consider how your child actually performs and functions. Some kids need more sleep than their peers do. Others need less.

Example (toddler): Sophie is 18 months old. Most children her age need 11-14 hours of total sleep each day, including naps. A few kids thrive on as little as 9-10 hours of total sleep. Some may need up to 15 hours.

Based on observation, Sophie’s parents estimate that she needs about 14 hours of sleep to feel cheerful, alert, and healthy. Sophie takes naps each day, accounting for about two hours of sleep. So she needs to sleep approximately 12 hours at night.

Sophie’s parents want her to awaken each morning at 7am, so they set their goal bedtime for 12 hours earlier — at 7pm.

Example (preschooler): Mario is 4 years old, and he no longer takes naps, so he must meet all his sleep needs at night. Experts recommend that kids Mario’s age get approximately 10-13 hours of total sleep time. They also acknowledge that some kids seem to do well when they fall an hour outside of this range.

After observing his behavior, Mario’s parents estimate that he requires about 10 hours of sleep. They want him to wake up each morning at 6:30am, so they determine that his goal bedtime is ten hours earlier — at 8:30pm.

2. Address factors that might interfere with your child’s ability to become drowsy at the desired bedtime.

Is your child taking naps too late in the day? Does your child consume caffeine? Is your child exposed to bright light in the evening, or too little bright light in the morning? This Parenting Science article about bedtime problems can help you troubleshoot.

Example (toddler): Sophie has been napping each day after 4pm. This is reducing sleep pressure in the evening, so her parents reschedule her afternoon nap so that it ends by 3pm.

Example (preschooler): Mario is in the habit of playing video games immediately before bedtime. The excitement — and bright light emitted by his device — might be delaying drowsiness. So his parents implement a new rule: No video games during the hour before bedtime.

3. Figure out when your child is currently in the habit of falling asleep each night, and then pick a new bedtime that is 15 to 30 minutes later.

Example (toddler): The ultimate goal for Sophie’s parents is a 7pm bedtime, but right now she falls short of this goal: Sophie doesn’t typically fall asleep each night until 7:45 pm. So Sophie’s parents reschedule bedtime for 8pm.

Example: Mario’s parents want him to fall asleep each night at 8:30pm. But currently, Mario doesn’t fall asleep each night until approximately 10pm. So Mario’s parents reschedule his bedtime for 10:15pm.

4. Keep your child awake (with calm, pre-sleep activities) until the newly-appointed bedtime arrives.

Why? Remember: Until now, your child has been associating bedtime with conflict, alertness, or a failure to fall asleep. You want to help your child to learn a new association — one that connects bedtime with an easy transition to sleep. If your child falls asleep before bedtime, you’ll have missed that learning opportunity.

5. Observe how your child responds to the new bedtime. How long does it take your child to fall asleep? And make the appropriate adjustments.

If your child falls asleep within 15 minutes, remain on this new schedule for one additional night.

Example: Bedtime is announced at 10:15pm, and Mario falls asleep within 15 minutes. The next night, Mario’s parents continue with the 10:15pm bedtime.

If your child takes more than 15 minutes to fall asleep, make an adjustment: On the following night, make bedtime even later (by 15 to 30 minutes).

Example: Bedtime is announced at 10:15pm, but Mario stays awake until 10:40pm. So the next night, Mario’s parents announce bedtime at 10:30pm.

5. Once your child has experienced two consecutive nights of success with the same bedtime — falling asleep within 15 minutes — introduce a slightly earlier bedtime.

Example: Bedtime is set for 10:15pm, and for two nights in a row, Mario falls asleep promptly. So on the following night, Mario’s parents set bedtime for 10pm.

6. Throughout this process, expose your child to crucial circadian cues. Awaken your child at the same time each morning — the wake-up time you identified as your goal.

Piazza and Fisher recommend that you do this, even if it means your child won’t get enough sleep for the day. Why?

You’re trying to reprogram your child’s circadian rhythms — to shift your child’s “internal clock” to an earlier schedule. And exposing your child to morning light — at the same time each day — is one of the most powerful tools for achieving this. (Read more about this in my article here.)

Moreover, if your child misses some sleep as a result, it can help speed up your child’s adjustment to the new schedule. Your child will build up more sleep pressure during the day, increasing his or her drowsiness at night.

What if your child has been in the habit of waking up much later? What if your goal wake-up time leaves your child too sleepy to function?

In this case, I think you need use your own judgment. It makes sense to me to avoid imposing a wake-up time if it would cause your child to lose more than an hour of sleep. You can arrive at your goal in steps.

Example: Mario is accustomed to waking up at 8:30am — two hours later than his goal wake-up time! That’s a big gap, so his parents decide to modify the official procedure. Instead of waking him at 6:30am, they begin the training by awakening him each morning at 7:15am. Then, over several days, they gradually shift Mario’s wake-up time to 6:30 am.

7. Continue with bedtime fading — making appropriate adjustments from night to night — until you’ve reached your goal bedtime.

How long this will this take? That depends on many factors, including the gap you’re trying to close. If you’re trying to get your child to fall asleep 30 minutes earlier at night, it might only take a few days to achieve your goal. If you’re trying to make an adjustment of more than one hour, training might continue for up to two weeks.

But what is the track record of this approach? Does the bedtime fading method work?

There’s reason to think so. For instance, consider the evidence from a study of bedtime tantrums. Researchers randomly assigned 36 young children to receive one of three experimental conditions:

- a program of Ferber method sleep training;

- a program that combined bedtime fading with the implementation of a pleasant, pre-bedtime routine (like taking a bath, and then reading a story); and

- a control condition.

After 6 weeks, kids in the two treatment programs experienced fewer tantrums than children in the control group did (Adams and Rickert 1989).

Then we have evidence of a somewhat different kind — studies that aren’t randomized, and don’t include control groups. Instead, researchers treat all participants the same way, and see if the treatment is linked with any changes.

In these studies, kids’ sleep habits are monitored before they begin bedtime fading, and then again after they’ve completed the program. And the outcomes are good.

For example, one of the biggest of these studies tracked the progress of 21 preschoolers in Australia. The children all had sleep problems — difficulty initiating sleep, trouble with frequent night wakings, or a combination of both. What happened?

It’s not clear that bedtime fading had any impact on night wakings, but researchers observed rapid improvements in

- the time it took kids to fall asleep at bedtime;

- the frequency of bedtime tantrums; and

- the total time kids spent awake at night, after falling asleep.

Before treatment, kids had taken an average of 23 minutes to fall asleep at bedtime. Two weeks late, this average had dropped to 12 minutes.

Among children who had been throwing bedtime tantrums, parents reported an average drop from 1.7 per week to 0.4 per week.

And total time spent awake at night (after sleep onset) had decreased too, from an average of 32 minutes to 24 minutes (Cooney et al 2018).

Other, smaller studies have tested variants of bedtime fading and reported similar results. Children end up falling asleep more quickly at bedtime, they get more sleep overall, and parents tend to report high satisfaction with the method (e.g., Piazza and Fisher 1991a; Piazza and Fisher 1991b; Piazza et al 1999; Sanberg et al 2018; Delamere et al 2018).

Where can I learn more about shifting my child’s “internal clock”? And other ways to improve my child’s sleep habits?

Check out my article, “How to reset your child’s internal clock for an earlier bedtime.”

In addition, I recommend these Parenting Science articles:

- “How to solve bedtime problems in children: Solutions for the science-minded”

- “15 baby sleep tips: Evidence-based advice for calmer, quieter, more restful nights”

- “Tech at bedtime: Do electronic devices cause sleep problems in children?”

- “Baby sleep deprivation: How to tell if your baby isn’t getting enough sleep”

- “Signs of sleep deprivation in children and adults”

References: Bedtime fading

Adams LA and Rickert VI. 1989. Reducing bedtime tantrums: Comparison between positive bedtime routines and graduated extinction. Pediatrics 84(5): 756-761.

Cooney MR, Short MA, Gradisar M. 2018. An open trial of bedtime fading for sleep disturbances in preschool children: a parent group education approach. Sleep Med. 46:98-106.

Delemere E, Dounavi K. 2018. Parent-Implemented Bedtime Fading and Positive Routines for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 48(4):1002-1019.

Kang EK and Kim SS. 2021. Behavioral insomnia in infants and young children. Clin Exp Pediatr. 64(3):111-116.

Piazza CC and Fisher W. 1991a. A faded bedtime with response cost protocol for treatment of multiple sleep problems in children. J Appl Behav Anal. 24(1):129-40.

Piazza CC, Fisher WW. 1991b. Bedtime fading in the treatment of pediatric insomnia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 22(1):53-6.

Piazza CC, Fisher WW, and Sherer M. 1997. Treatment of multiple sleep problems in children with developmental disabilities: faded bedtime with response cost versus bedtime scheduling. Dev Med Child Neurol. 39(6):414-8.

Sanberg SA, Kuhn BR, Kennedy AE. 2018. Outcomes of a Behavioral Intervention for Sleep Disturbances in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 48(12):4250-4277.

Content last modified 8/2023

Image credits:

Title infographic by Parenting Science

Image of girl under covers by Liderina / istock