Developmental toys and educational games for kids are relatively recent inventions. Do they work?

Throughout most of human history, children got little or no formal instruction. Instead, they learned by imitation, and by honing new skills through pretend play (Lancy 2008). Today, we know that play benefits brain development. It may promote problem-solving, too. And, as I explain elsewhere, certain types of fantasy play may help children develop better “executive function” skills, like the ability to stay focused.

But what about the toys that children play with? The board games and video games? Are there toys and games that make children into better students? Or better citizens?

Parents living in high-tech cultures are especially interested in toys that teach. But “smart” toys are a relatively recent invention. In fact, adult-designed toys are uncommon in non-industrial cultures, where children’s make-believe is mostly the reenactment of mundane, everyday adult activities (Power 2000).

By contrast, children living in complex, literate societies are often encouraged to engage in elaborate, pretend play, and that, says anthropologist David Lancy, makes sense: Such play might improve a child’s academic readiness, and enhance his or her long-term economic prospects (Lancy 2008).

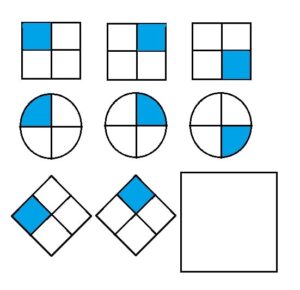

So it seems reasonable to ask if toys can provide kids with meaningful educational experiences, and surely the answer is yes. For example, consider how intelligence is measured in standardized tests. In his book, Intelligence and How to Get It: Why Schools and Cultures Count, psychologist Richard Nisbett notes that Raven’s progressive matrices — an intelligence test often touted as “culture-free” — is steeped in culture (Nisbett 2009). Take a look at a typical question (pictured here).

Test takers are meant to look at the first two rows and identify the pattern. Next, they looks at the bottom row. What should come next — in the empty box?

If we grant that people perform better when they are familiar with a task, then clearly there are experiences that can help us solve this problem. A test-taker will have an advantage if he or she is familiar with

- regular geometric shapes

- analog clocks and clockwise movement

- the idea that gradual, stepwise changes can be depicted by a sequence of images

- the assumption that it’s okay to generalize a rule from only two prior examples

You can probably think of more. But the point is this: Each of these elements must be learned, and some people—including virtually all of our ancestors—didn’t learn them.

That’s one reason why IQ scores have risen over the last century. It’s not that people have become intrinsically smarter. It’s that their culture is doing a better job training them in the areas that help people succeed on IQ tests (Flynn 2007). And where does this training take place? At school, yes. But other places, too. At home, in books, on television, on the computer, and through exposure to toys and educational games.

What’s true for learning about shapes is doubtless true for other things—like acquiring advanced language skills or developing “number sense.”

So the real question is: Which toys and games offer the most effective educational experiences? Unfortunately, there isn’t much research to guide us. For example, the vast majority of supposedly instructional electronic games have not been rigorously tested for their educational effects. Then again, there has been surprisingly little rigorous research on the effects of playing chess. Or even on the effects of playing with blocks.

Still, we have good reason to think that some toys and games provide kids with more than mere entertainment.

Which toys and educational games are supported by research?

In these pages, I review what published studies tell us about toys and educational games for kids. If you are wondering what to spend your money on, a good place to begin is my article about construction toys. As I note there, toy blocks are linked with better language development and higher achievement in math. There is also reason to think that construction toys hone spatial skills and inspire kids to follow career paths in science, engineering, and technology.

In addition, there is experimental evidence that certain board games improve math skills. For instance, when young children (aged 4 to 6) play board games with traditional dice (each face showing a different number of dots), they may improve their counting skills (Gasteiger and Moeller 2021).

More generally, I think it’s reasonable to assume that many board games promote analytical skills—if we combine them with explicit lessons in critical thinking. For more information, see my evidence-based articles about board games and teaching critical thinking to kids. Looking for additional recommendations? Consider these:

- Tangram puzzles have been endorsed by The National Council of Teacher’s Mathematics (NCTM). Learn more about it from this Parenting Science article, which includes a printable template for making a set of tangrams at home.

- Preschoolers can boost their number sense by playing these DIY educational games.

- Mancala games encourage kids to count and strategize. And you can easily create your own game at home. See my overview and guide to the rules.

- Cooperative board games may foster social and critical thinking skills. They are also a good choice for young children, and a refreshing alternative to old fashioned preschool games like Candy Land™, which can be tedious to play. Read more about the benefits of cooperative play in this Parenting Science article.

- Researcher-designed party games may help older kids “tune in” to the perspectives of other people. As I explain in my round-up of evidence-based social skills activities, teenagers who played Buffalo: The Name Dropping Game™ were subsequently more interested in fighting social stereotypes (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

- Brain scan studies suggest that young children practice their “mind-reading” skills (tuning into thoughts, feelings, and desires) when they play with dolls (Hashmi et al 2022), and researchers suspect that kids learn to reason about possible words when they engage in pretend play (Wente et al 2022). So even a simple, low-tech doll can be considered an educational toy.

- Preschoolers can hone their executive function skills — including aspects of attention and impulse control — by playing social games like “Red Light, Green Light” (Tominey and McClelland 2009). For more information, see recommendation #4 in my article, “Teaching self-control: Evidence-based tips.”

What about video games?

As noted above, there hasn’t been a lot of rigorous research about the educational effects of video games. On the negative side, there is evidence that playing violent video games can put us in a frame of mind — if only briefly — that makes us less sympathetic to the plight of victims. There is also research suggesting that some kids suffer from video game “addiction.”

But there is good news, too. Studies suggestion that certain kinds of video games can enhance visual attention skills, and maybe even help children with dyslexia learn to read. For more inforation, see my article, “Video games and attention: Gaming enhances some attention skills, and hinders others.”

In addition, experiments indicate that some “action” video games can improve visual-spatial performance, specifically the ability to track multiple objects in a fast-moving setting (Oei and Patterson 2015; Oei and Patterson 2013). And some games — like “Kerbal Space Program” (for high school students), and these recommendations from CommonSense.org — can help kids master science concepts.

More about toys and games for kids

For more suggestions, visit the Parenting Science Amazon store. A portion of your purchase will help support this site. And check out my Parenting Science article about gendered play: “Girl toys, boy toys, and parenting: The science of toy preferences in children.”

References: Developmental toys and educational games for kids

Flynn JR. 2007. What is intelligence? Cambridge University Press.

Gasteiger H and Moeller K. 2021. Fostering early numerical competencies by playing conventional board games. J Exp Child Psychol. 204:105060.

Hashmi S, Vanderwert RE, Paine AL, Gerson SA. 2022. Doll play prompts social thinking and social talking: Representations of internal state language in the brain. Dev Sci. 25(2):e13163.

Kaufman G and Flanagan M. 2015. A psychologically “embedded” approach to designing games for prosocial causes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(3), article 1.

Lancy DF. 2008. The anthropology of childhood: Cherubs, chattel, and changelings. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nisbett RE. 2009. Intelligence and how to get it. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Oei AC and Patterson MD. 2015. Enhancing perceptual and attentional skills requires common demands between the action video games and transfer tasks. Front Psychol. 6:113.

Oei AC and Patterson MD. 2013. Enhancing cognition with video games: a multiple game training study. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58546.

Power TG. 2000. Play and exploration in children and animals. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Priewasser B, Roessler J, Perner J. 2013. Competition as rational action: why young children cannot appreciate competitive games. J Exp Child Psychol. 116(2):545-59.

Tominey S and McClelland M. 2011. Red Light, Purple Light: Findings From a Randomized Trial Using Circle Time Games to Improve Behavioral Self-Regulation in Preschool. Early Education & Development 22(3): 489-519.

Wente A, Gopnik A, Fernández Flecha M, Garcia T, Buchsbaum D. 2022. Causal learning, counterfactual reasoning and pretend play: a cross-cultural comparison of Peruvian, mixed- and low-socioeconomic status U.S. children. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 377(1866):20210345.

Content of “Smart toys and educational games for kids” last modified 12/2022. Portions of the text derive from a previous version of this article, written by the same author.

image illustrating the type of questions found in Raven’s Progressive Matrices copyright Parenting Science

image of kids playing board game by Frolphy / shutterstock