The need for evidence-based education

When should kids start school? What should we teach them? How should we teach them? Where should we teach them? Research can help us answer these questions. And we should pay attention.

When schools adopt the wrong programs and practices, money gets wasted. Students may get steered in directions that limit creativity or sap motivation. They may experience conditions that increase the development of behavior problems. Kids might even get misdiagnosed with learning or attention problems — like ADHD.

Unfortunately, the research that is most helpful for assessing educational practices — randomized, controlled studies of real-world practices — isn’t very common. So until there is more rigorous, applied research, we have to make do.

Insights from pure research, like this experiment on the effects of negative feedback, suggest new approaches to teaching. And we can make informed guesses based on correlations, cross-cultural comparisons, and quasi-experimental studies conducted in schools.

Below is a guide to evidence-based research on variety of school topics, including teaching self-discipline, preventing summer learning loss, assessing homeschooling outcomes, and determining the appropriateness of homework for young children,

I’ll continue to add new articles over time.

When should formal schooling begin?

To profit from schooling, kids need a certain amount of maturity. They need to control their impulses and pay attention. They need a working memory capacity big enough to keep a teacher’s instructions “in mind” as they work. And they need a certain amount of emotional and social sophistication.

When do these traits come together?

Around the world, most societies have assumed kids aren’t ready until they are at least 5-7 years old. But in some places, academic instruction begins much earlier. In the United Kingdom, formal schooling now begins at the age of 4. And some American preschools have adopted curricula once reserved for primary schools.

Is this unprecedented push for early academics a good idea?

Human beings are flexible creatures, and it’s possible for them to thrive under a variety of conditions. So the novelty of early academics isn’t necessarily a mark against them. But some people worry about the consequences of pushing young children too hard.

To date, the most relevant experimental evidence against early academics comes from the labs of Alison Gopnik and Laura Schultz.

In two different studies, 4-year-old children were presented with new toys and given opportunities to play with them. Some kids were guided by an authoritative adult who told them how to operate the new toys. Other kids were accompanied by an adult, but received no instructions.

The difference mattered.

When given adult instructions, kids tended to accept those instructions uncritically. If the advice turned out to be illogical, they didn’t seem to notice. And the kids showed less initiative and creativity during play.

You can read more about these experiments here.

Is early schooling too academic for young children?

There is no clear answer to this, but studies hint that – for many kids – there is a mismatch between their capabilities and the expectations of the classroom.

On the one hand, Mimi Engels and her colleagues (2013) present evidence that American kindergarteners have been taught mathematics concepts they’ve already mastered, and exposure to these redundant classroom lessons has been linked with poorer academic progress during the kindergarten school year.

On the other hand, it seems likely that some developmentally-normal kids are being held to behavioral standards that are unrealistic.

One study estimates that 20% of American kindergarteners have been inappropriately diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder because they are younger, and therefore less socially mature, than other kids in the classroom (Elder 2010). To read more about the difficulty of diagnosing ADHD, click here.

But what about the idea of teaching self-control? Doesn’t early education teach children how to behave in more mature ways? If you send a three-year-old to preschool, won’t he learn to pay attention, follow directions, and control his impulses?

There may be ways to foster these skills in very young children. But a recent study suggests that most American preschools, as they exist today, aren’t having significant effects in these areas (Skibbe et al 2011).

So I think we need to test the idea that very early classroom experiences can substantially accelerate the development of attention and what psychologists call executive control. And we should keep in mind that impulsivity isn’t always bad.

A study tracking elementary school kids found that young children who blurted out answers to arithmetic problems made more errors in the short-term, but developed into faster and more accurate mathematicians by the sixth grade (Bailey et al 2012). Researchers think the kids’ willingness to risk a wrong answer led to more learning opportunities and ultimate mastery. For details, see this evidence-based education blog post for BabyCenter.

Are kids better off when we provide them with outdoor learning opportunities?

Studies suggest that nature experiences reduce stress, improve moods, boost concentration, and increase a child’s engagement in school. Read more about it here.

How important are student-teacher relationships?

When people talk about improving schools, they often focus on curricula, test scores, and educational technology. But what about the personal factor? The relationships that individual children have with their teachers?

Many studies have reported that kids who feel liked and supported by their teachers do better in school, and it’s not merely because children who appeal to teachers tend to be more attentive or studious. Kids with behavior problems and other risk factors for poor outcomes seem to benefit the most from having emotionally-supportive teachers.

Moreover, the benefits of a good relationship are far-reaching and substantial.

To read more about student-teacher relationships – including their effects on a child’s stress-response system, long-term mathematics achievement, and problem-solving speed – see my Parenting Science review of the research.

Can we help kids cope with school stress?

Stress isn’t necessarily harmful. We need a certain amount of stress to feel challenged and fulfilled. But some kids experience the bad sort of stress, and it can damage health and interfere with academic achievement.

Not surprisingly, school bullying is one source of toxic stress (Fekkes et al 2006). Chronic anxiety about high-stakes exams and fear of teacher punishment are others (Hesketh et al 2010). But kids facing unusual levels of hostility or performance pressure aren’t the only ones who find school stressful.

In a recently published study, Dutch investigators analyzed hair samples from 4-year-olds to measure concentrations of the stress hormone cortisol. When the researchers compared hormone levels before and after the children had begun elementary school, they found that cortisol levels had increased after school entry, particularly in temperamentally fearful kids (Groeneveld et al 2013).

Another study, conducted in Germany, suggests that the average elementary school child experiences higher afternoon cortisol levels as the school week progresses – a sign that the stress response system is under strain (Ahnert et al 2013). Perhaps many kids are more stressed than we realize.

If so, there are remedies. The German study also found that the kids with the least abnormal hormone profiles were the ones involved in warm, supportive student-teacher relationships

And, as noted above, there is mounting evidence that nature experiences reduce stress. So some evidence-based education advocates believe we can help kids cope with school stress by engaging them in outdoor lessons.

Other research suggests that having just one good friend can buffer kids from the harmful psychological effects of peer rejection and bullying (Bagwell et al 1998; Hodges et al 1999; Pederson et al 2007; Oh et al 2008).

And parents can help kids cope by offering emotional warmth and promoting a resilient, effort-based attitude about achievement.

For more information about school-related stress, see my article, “The dark side of preschool,” and my blog posts

- “Smart first graders are choking on math anxiety: How to nip it in the bud”

- “Back to school stress: Helping kids unwind”

For other information about helping children cope, see my articles about friendship in children and the importance of sensitive, responsive parenting.

What about classroom discipline?

Students need to follow directions in class and to treat others with respect and kindness. What’s the best way to achieve these goals?

In one intriguing experiment, students attending a punitive, disciplinarian school showed a greater tendency to lie about their transgressions or mistakes. They’d obviously learned the value of being sneaky (Talwar and Lee 2011).

Other studies suggest that spanking is less effective than other, non-physical forms of punishment.

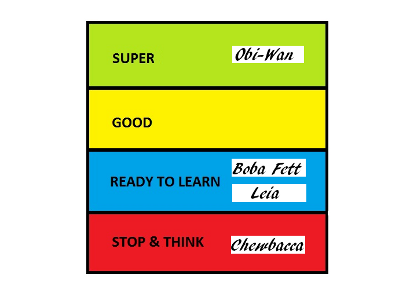

And research on the counterproductive effects of public shaming makes me question the routine use of classroom behavior charts to enforce discipline.

These points suggest that a more positive approach works better.

As I explain in this article, an intriguing experiment hints that we can encourage kids to better regulate their own behavior with a few, almost magical words.

And a variety of studies suggest that children’s self control depends, in large part, on the way we treat them. For evidence-based information on how we can foster self-control in children, see this Parenting Science review.

Should we group students by age?

The modern classroom of 25+ students–all approximately the same age–is often taken for granted. How else would we educate kids? But from the standpoint of history and evolution, it’s an unusual approach.

Throughout most of human history, kids spent their time in mixed-aged playgroups.

The idea of herding together a large cohort of children the same age–and separating them from everyone else, including most adults–would have been considered strange.

What are the educational consequences of an aged-based classroom? It’s more efficient from the standpoint of educating large groups of kids. But individuals might miss out.

From a social and emotional standpoint, older kids may lose important opportunities to practice altruism, empathy, and perspective-taking with younger children.

Younger kids might miss opportunities to play with older, more sophisticated kids. For a brief discussion of research about the benefits of mixed age groups, read by blog post on the subject.

How much homework should kids do?

Some writers–like Alfie Kohn–argue that nobody should do homework. I don’t agree. If kids are headed to college–or any white collar job–they will need read a lot, and read critically. They will need to organize and complete written projects on their own. Today’s undergraduates are often unprepared for this sort of work. Perhaps some of these students aren’t doing enough homework in high school.

But I have serious misgivings about the new trend of assigning substantial amounts of homework to young children. There is very little research on the subject, but good reason for concern.

What should be a part of your child’s curriculum?

Science, critical thinking, and evidence-based education

Everybody agrees that reading, writing, and mathematics are core subjects. What else should be required?

I’d like to see more science topics incorporated into the everyday curriculum of preschool and primary school students.

This page discusses evidence-based education practices for teaching science to kids, and includes links to science activities.

I’d also like to see critical thinking become a core academic subject in school.

A recent study of American undergraduates suggests that almost 40% of college students are graduating without making any improvements in their critical thinking abilities.

That’s alarming, but I’m even more concerned that we aren’t teaching critical thinking before college. Because it might make a big difference.

Research suggests that middle school students make substantial improvements in their analytical abilities when we teach them the formal principles of logic and rationality.

Kids may also learn a lot about critical thinking when we teach them to debate. Read about an intriguing experiment on middle school students here.

What about other additions to your child’s curriculum?

Spatial skills are critical for many careers, not just in the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), but also in mechanical work and the arts. There is good evidence that children can improve their spatial intelligence through training.

Some tactics aren’t obvious. For instance, researchers suspect that young children improve spatial skills when they practice fine motor tasks, like tracing and copying geometric designs. For more ideas about how to promote spatial intelligence, see these evidence-based tips.

There is also compelling evidence that kids will become better students–and improve their math scores–when they are taught about the plasticity of intelligence. This may be especially important in Western cultures where many people tend to believe that intelligence is fixed at birth.

And computers may be helpful for individualized drills and practice in math, reading, and other topics.

James Kulik (2003) analyzed almost 400 studies of computers in the classroom—including 61 controlled studies published after 1990.

Overall, he found that elementary and high school students using computer tutorials made substantial gains over kids in control groups–more than enough to boost their test scores from a “C” average to a “B” average.

But of course it’s crucial to identify good educational software.

And what about the humanities — like literature, music, and the visual arts? When schools lacking funding, programs in the arts are usually the first to get eliminated. It might seem like the only option, but we should consider the potential cost.

Appreciating and participating in the arts is one of the things that make life worth living. But even putting aside the immediate psychological rewards, studying the humanities has long-term, practical consequences. Experiments confirm that music lessons shape the brain and alter perception. Reading stories and novels can boost perspective-taking skills (Ornaghi et al 2014; Kidd and Castano 2013). And researchers report links between health, well-being, and participation in creative activities (Cuypers et al 2012).

There is also evidence that exposure to fantasy fiction makes kids more creative — an outcome relevant to success in business and STEM fields as well as the arts (Subbotsky et al 2010).

Why kids need recess

In some places, traditional recess–a time for kids to take a break from their studies and play freely outdoors–is being eliminated or replaced.

This worries many people who have strong intuitions about the importance of recess. It’s a powerful folk belief. Does the research support it? I think it does.

Randomized, controlled studies on overweight children suggest that aerobic exercise can improve attention, self control, as well as academic performance. In some studies, kids enjoyed a boost in their math skills and even their IQ scores.

And experiments on rodents have revealed that cardiovascular exercise triggers brain cell growth and facilitates learning. But these effects have been associated with voluntary exercise–not forced exercise.

Read more about these studies–and their implications for evidence-based education– here.

References: Evidence-based education

Bonawitz E, Shafto P, Gweon H, Goodman ND, Spelke E and Shultz L. 2011. The double-edged sword of pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery. Cognition 120(3): 322-330.

Buchsbaum B, Gopnik A, Griffiths TL, and Shafto P. 2011. Children’s imitation of causal action sequences is influenced by statistical and pedagogical evidence. Cognition 120(3): 331-340.

Cuypers K, Krokstad S, Holmen TL, Skjei Knudtsen M, Bygren LO, Holmen J. 2012. Patterns of receptive and creative cultural activities and their association with perceived health, anxiety, depression and satisfaction with life among adults: the HUNT study, Norway. J Epidemiol Community Health. 66(8):698-703.

Davies P. 1999. What is evidence-based education? British Journal of Educational Studies 47(2) 108-121.

Kidd DC and Castano E. 2013. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science. 342(6156):377-80.

Kulik J. 2003. Effects of using instructional technology in elementary and secondary schools: What controlled evaluation studies say. Arlington, Virginia: SRI International.

Ornaghi V, Brockmeier J, Grazzani I. 2014. Enhancing social cognition by training children in emotion understanding: A primary school study.J Exp Child Psychol. 119:26-39. – See more at:

Slavin RE. 2002. Evidence-based education policies: Transforming educational practice and research. Educational Researcher 31(7): 15-21.

Subbotsky E, Hysted C, Jones N. 2010. Watching films with magical content facilitates creativity in children. Percept Mot Skills 111(1):261-77.

Content of “Evidence-based education” last modified 3/14

image of boys working together on a computer by PeopleImages.com – Yuri A / shutterstock