What is sensitive, responsive parenting? It’s really pretty simple. First, you tune into your child’s emotions, concerns, and needs. That’s the sensitive part. Then you provide your child with the appropriate level of support and reassurance. That’s the responsive part. Simple, and very powerful.

For years, researchers have noticed that that sensitive, responsive parenting is linked with better cognitive outcomes for children. For example, children learn language more rapidly when caregivers respond promptly and contingently to kids babies do (Tamis-Lamonda et al 2014; Bornstein et al 2020). Preschoolers develop better problem-solving ability, attention skills, and school readiness when their parents are sensitive and responsive (Landry et al 2003; Landry et al 2006; Yousafzai et al 2016).

But there may be important health benefits, too. Research suggests that sensitive, responsive parenting can protect children from chronic disease and toxic stress.

To see what I mean, consider kids living in neighborhoods blighted by poverty and crime.

These kids experience atypical fluctuations of the stress hormone cortisol, putting them at increased risk for a variety of metabolic conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

There is also evidence linking stress and economic adversity with chronic inflammation — a condition that can trigger atherosclerosis, autoimmune disorders, and cancer (Milaniak and Jaffee 2019; Muscatell et al 2020; Kuhlman et al 2020).

For instance, when University of British Columbia psychologists Gregory Miller and Edith Chen tested adolescents for biochemical markers of inflammation, they found that kids of lower socioeconomic status were more likely to develop a “pro-inflammatory phenotype” (Miller and Chen 2007).

Can parents protect kids from the effects of toxic stress and inflammation?

The idea fits with our everyday observations. Sensitive, responsive parents make children feel safe. They make kids less suspicious of other people, and therefore more relaxed. Secure, relaxed children experience fewer spikes of cortisol, and when they do get stressed, they recover more quickly.

In addition, by teaching their kids how to regulate their own emotions, parents help children develop effective self-soothing mechanisms. Kids learn how to cope, even when their caregivers aren’t around.

Together, these factors should help protect kids from the physiological wear-and-tear caused by chronic stressors (Repetti et al 2002; Chen et al 2011).

So Chen and Miller sought to test the idea by inquiring into the early life experiences of people who grew up poor.

In one study, they asked 53 healthy young adults about their family relationships. Study volunteers who reported feelings of greater warmth toward their mothers showed fewer signs of systemic inflammation (Chen et al 2011).

In another study, the researchers explored the effects of parental warmth and sensitivity on the development of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of medical conditions that includes central obesity, high blood pressure, and insulin resistance (Miller et al 2011).

The researchers asked more than 1200 middle-aged Americans questions about their parents. Questions like, “How much did your parent understand your problems and worries?” and “How much time and attention did s/he give you when you needed it?“

Then the researchers examined participants for symptoms of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of health problems that includes high blood pressure, impaired glucose control, and the accumulation of abdominal fat.

As expected, people who grew up in low socioeconomic status (SES) households were more likely to have these symptoms. But about 45% of the people with low SES childhoods were symptom-free. And these healthy people were more likely to have had nurturing mothers.

In fact, among kids with the most nurturing mothers, there was no correlation between SES and poor health status.

To put this in perspective, the researchers also tested the effects of being upwardly mobile. If you were born relatively poor, but achieved higher SES as an adult, did you enjoy better health?

Surprisingly, the answer was no. Not when it came to symptoms of metabolic syndrome. The researchers couldn’t detect any difference between people who stayed poor and people who moved up the socioeconomic ladder.

Of course, we should be mindful that these studies didn’t include any direct observations of parenting. It’s all based on what adult children felt or remembered about their parents. How can we be sure that those memories were accurate? We can’t.

But another team of investigators — led by Allisson Farrel — has taken a somewhat different approach. Instead of relying on people’s childhood memories, they analyzed decades of data collected on more than 160 individuals as they grew from infancy to adulthood. Stressful life evens were logged as they happened. Families were interviewed at many time points along the way. Parents were observed — in real time — while they interacted with their kids. And what did the researchers discover?

Once again, sensitive, responsive parenting was linked with better adult outcomes. Maternal sensitivity protected kids living in stressful environments from developing health problems as adults (Farrell et al 2017; Farrell et al 2019).

Is this proof that sensitive, responsive parenting has a lasting impact on health?

These are correlations only, and correlations can’t prove causation. For instance, none of these studies controlled for genetic factors. Maybe nurturing parents are more likely to carry genes that confer better health, and they pass these genes along to their kids.

And what about fathers? In that study of the 1200 middle-aged adults, Miller and his colleagues didn’t find evidence linking health benefits t nurturing dads. Just moms. Is that because the fathers in this study were less involved with childcare? Future studies are needed to rule out alternative explanations.

But in the meantime, there is other evidence to consider.

For example, experiments on nonhuman animals suggest that family interactions have a profound impact on health.

When researchers have cross-fostered rat pups — assigned them to be raised by adoptive mothers — they have found strong evidence for the power of affectionate care. Rats raised by highly responsive mothers show less stress reactivity as adults (Francis et al 1999; Meaney 2001).

And in experiments on zebra finches, investigators found that a bird’s lifespan depended on the temperament of its companions. Anxious, easily “stressed out” finches lived longer when they when they were paired with calmer, more resilient companions (Monaghan et al 2012).

There are also intriguing observational studies tracking human children over the short-term.

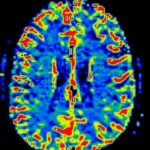

For example, an fMRI study suggests that sensitive, responsive parents can protect kids from the brain-shrinking effects of toxic stress (Luby et al 2013).

In addition, research on babies exposed to prenatal stress found that 7-month-old infants showed signs of better emotional regulation if their mothers had exposed them to lots of physical affection (Sharp et al 2012).

Follow-up studies confirm the effect lasts into the toddler years, and researchers have connected the phenomenon to epigenetics, or long-term alterations of DNA function (Sharp et al 2015; Pickles et al 2016).

Early life stress can silence genes that help regulate an individual’s stress response system. But tactile affection seems to reverse the process (Murgatroyd et al 2016).

If true, scientists may have uncovered a key mechanism for parental responsiveness and affection to impact health. But regardless of the mechanisms, researchers are amassing an increasingly impressive case for the health benefits of responsive, sensitive parenting.

More information

For more information about parental warmth and child outcomes, see these Parenting Science articles:

- Secure attachments protect kids from toxic stress

- Oxytocin affects social bonds and our responses to toxic stress. Can we influence oxytocin in children?

- How do children respond to a mother’s voice?

- The science of attachment parenting

To read more about reasoning with children, see my article on the authoritative parenting style. And for practical parenting tips, see this guide to positive parenting.

References: Health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting

Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Bohr Y, Abdelmaseh M, Lee CY, Esposito G. 2020. Maternal Sensitivity and Language in Infancy Each Promotes Child Core Language Skill in Preschool. Early Child Res Q. 2020 2nd Quarter 51:483-489

Chen E, Miller GE, and Parker KJ. 2011. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull. 2011 Jul 25. [Epub ahead of print]

Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS, Cole SW. 2011. Maternal warmth buffers the effects of low early-life socioeconomic status on pro-inflammatory signaling in adulthood. Mol Psychiatry. 16(7):729-37.

Farrell AK, Waters TEA, Young ES, Englund MM, Carlson EE, Roisman GI, Simpson JA. 2019. Early maternal sensitivity, attachment security in young adulthood, and cardiometabolic risk at midlife. Attach Hum Dev. 21(1):70-86.

Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ. 1999. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 286(5442):1155-8.

Kuhlman KR, Horn SR, Chiang JJ, Bower JE. 2020. Early life adversity exposure and circulating markers of inflammation in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 86:30.

Landry SH, Smith KE, and Swank PR. 2003. The importance of parenting during early childhood for school-age development. Dev Neuropsychol. 24(2-3):559-91.

Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. 2006. Responsive parenting: establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Dev Psychol. 42(4):627-42.

Luby J, Belden A, Botteron K, Marrus N, Harms MP, Babb C, Nishino T, Barch D. 2013. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: the mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatr. 167(12):1135-42.

Meaney MJ. 2001. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 24:1161-92.

Milaniak I and Jaffee SR. 2019. Childhood socioeconomic status and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2019 May;78:161-176.

Miller G and Chen E. 2007. Unfavorable socioeconomic conditions in early life presage expression of proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence. Psychosom Med. 69(5):402-9.

Miller GE, Lachman ME, Chen E, Gruenevald TL, Karlamangla AS, and Seeman TE. 2011. Pathways to resilience: Maternal nurturance as a buffer against the effects of childhood poverty on metabolic syndrome at midlife. Psychological Science (12):1591-9.

Monaghan P, Heidinger BJ, D’Alba L, Evans NP, and Spencer KA. 2012. For better or worse: reduced adult lifespan following early-life stress is transmitted to breeding partners. Proc Biol Sci. 279(1729):709-14.

Murgatroyd C, Quinn JP, Sharp HM, Pickles A, Hill J. Effects of prenatal and postnatal depression, and maternal stroking, at the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Transl Psychiatry. 5:e560.

Muscatell KA, Brosso SN, Humphreys KL. 2020. Socioeconomic status and inflammation: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 25(9):2189-2199.

Pickles A, Sharp H, Hellier J, Hill J. 2016. Prenatal anxiety, maternal stroking in infancy, and symptoms of emotional and behavioral disorders at 3.5 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Jul 27. [Epub ahead of print].

Repetti RL, Taylor SE and Seeman TE. 2002 Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin 128: 330-366.

Sharp H, Hill J, Hellier J, Pickles A. 2015. Maternal antenatal anxiety, postnatal stroking and emotional problems in children: outcomes predicted from pre- and postnatal programming hypotheses. Psychol Med. 45(2):269-83.

Sharp H, Pickles A, Meaney M, Marshall K, Tibu F, Hill J. 2012. Frequency of infant stroking reported by mothers moderates the effect of prenatal depression on infant behavioural and physiological outcomes. PLoS One. 7(10):e45446.

Tamis-LaMonda CS, Kurchirko Y, and Song L. 2014. Why is infant language learning facilitated by parental responsiveness? Current Directions in Psychological Science23(2): 121-12.

Yousafzai AK, Obradović J, Rasheed MA, Rizvi A, Portilla XA, Tirado-Strayer N, Siyal S3, Memon U. 2016. Effects of responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions on children’s development and growth at age 4 years in a disadvantaged population in Pakistan: a longitudinal follow-up of a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet Glob Health. 4(8):e548-58.

Content of “The health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting” last modified 11/2021

Image of mother and baby gazing into each’s others eyes by Matrix Images / istock

Image of brain MRI by wenht/ istock