Peer pressure and social conformity starts long before adolescence. When faced with a choice between telling the truth and backing a popular falsehood, even 4-year-old children will buckle. Yet kids also possess the ability to question — and even reject — majority opinion. What can we do to encourage children to think for themselves?

You and three other people are sitting in adjacent booths, and you’ve each got a copy of the same book.

Open to the first page. You see a picture of a family of bears. On the next page, you see a picture of just one member of that family.

Now suppose I ask you to tell me who’s featured in the solo picture.

Is it Papa Bear? Mama Bear? Baby Bear? You’ve heard the other people claim that the character is Papa Bear. But you see very clearly that it’s Baby Bear. What do you say?

It probably depends on a lot of things. Your motivation, your confidence, the social context. Does it really matter what you say? Is your answer going to be public? Do you live in a culture that puts a premium on fitting in?

And what about your age? We know that many adults are inclined to give into social pressure. But how early does this tendency emerge? When does it start?

You might be thinking of adolescence. But try again. Researchers have documented the phenomenon among little kids.

One of the breakthrough studies was conducted at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, where psychologists Daniel Haun and Michael Tomasello performed this “Baby Bear” test on 4-year-olds.

The researchers had children sit in groups of 4, with each child in a private booth that allowed him or her to hear, but not see, the other kids. The children were given picture books they believed to be identical. But in fact, one in four books varied. Some of the pictures were different.

The test went like this: Kids were asked to turn to the correct page in their books, and then, one at a time, asked to report what they saw.

There were 18 trials in all. In 12 trials, the books all showed the same images. In the other 6 trials, the images differed and the child in possession of the odd book faced a conflict. Report what you see, or go along with the crowd.

In total, 96 kids participated. Twenty four of them were randomly selected to receive the odd book. And 18 out of 24 of these children conformed to the (inaccurate) majority opinion at least once. Ten kids did it on most trials.

Sit a child down with 3 other preschoolers, and she might decide to agree that it’s Papa Bear, when she really knows it’s Baby Bear.

Were the kids who changed their answers motivated by social pressure? Or was something else going on? Maybe they were just confused?

To check, Haun and Tomasello ran a second experiment in which kids were sometimes permitted to answer the question privately (so the other kids wouldn’t know).

In those cases, kids still occasionally changed their answers to conform. But not as much.

Children were most likely to conform when they knew other people were listening.

So it seems this really was about peer pressure — about going with the flow.

What exactly are children thinking when they make these decisions?

That isn’t clear. Maybe kids are just applying lessons learned by trial-and-error. They’ve gotten into conflicts with other kids before. They’ve learned that they get into less trouble when they conform.

Or maybe, suggest Haun and Tomasello, something more sophisticated is going on. Kids are thinking about how other people see them. They are consciously grooming a public image.

Either way, we’ve got evidence that young children are trying to fit in. Even when that means paying lip service to something that doesn’t make sense.

And other studies back this up.

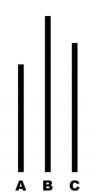

For example, Kathleen Corriveau and her collleagues (2013) asked 3- and 4- year-olds to make a simple spatial judgment about the lengths of different lines.

“See these three lines on the screen? Can you point to the big one?”

Once again, most of the kids caved to majority opinion — even when it was clearly wrong. And once again, the conformity depended on the presence of an audience.

When preschoolers were asked to make their judgment in private — to vote without any witnesses watching — they were more likely to stand their ground and speak the truth.

If young children are willing to lie about things like bear pictures and lines, are they also willing to bend on social and moral issues?

That’s what Elizabeth Kim and her colleagues wanted to know, so they ran a new set of experiments.

One hundred and thirty-two young kids participated, ranging in age from 2 to 6.

And these children weren’t just tested on their judgments of simple spatial relationships (“which line is bigger?”). They were also tested on their reactions to social and moral transgressions.

During the experiment, each study participant was presented with several different scenarios of wrongdoing.

The child was shown a picture of another kid committing a transgression, and asked to offer his or her judgment about it.

For example, the child might see an image depicting a scenario like this one, and be asked:

“Is it okay or not okay for the boy to do this (to call someone names)?”

Next, after the study participant had weighed in on four different transgressions, the adult presented the participant with additional information — a video clip of two other kids responding to the same scenarios.

“I’m going to show you some kids who are also going to be shown some pictures and asked if they think something is okay or not okay. After that, I’m going to ask you whether you think something is okay or not okay. Let’s watch.”

And that’s where the social pressure came into it. The children in the video clip looked over the same scenarios, and they gave their approval to all of the transgressions depicted — including transgressions of social convention (e.g., taking out a toy during snack time) and transgressions of morality (e.g., calling another child names).

After each transgression was discussed, the adult experiment followed up with the crucial query. For example:

“Oh look. These two little kids think that it is okay to do this. What do you think? Is it okay or not okay for a child to call someone names?”

As noted, the study participants also got questioned about spatial relationships. So the researchers were able to compare how social pressure affected judgments about each type of phenomenon — social conventions, moral issues, and spatial relationships. How did it all turn out?

The results: Kids were more likely to conform on social and moral issues

In this study, many kids stayed true to their original judgments. But some caved at least once, and the conformity effect was actually strongest for the social and moral judgments. Not for the judgments about spatial relationships.

About 20% of the children gave into pressure when it came to violations of social conventions.

And nearly 35% of the children reversed their judgments about at least one of the moral transgressions. They now said it was “okay” to call someone names, or to tease another child.

So it didn’t take much to flip their answers — just a couple of peers in a video clip, and an adult asking the same question twice (Kim et al 2016).

Does this mean we’re doomed? That human beings are destined to conform to peer pressure, authoritarian dogma, mob hysteria?

What these studies really tell us is that we’re very susceptible. From early childhood, we’re inclined to go with the flow.

But that doesn’t mean that conformity is mindless.

It isn’t as if young children imitate whatever they see other individuals doing — even if it doesn’t make sense to them. They are also looking for cues of approval. In one experiment, preschoolers didn’t imitate apparently pointless behavior unless adult onlookers appeared to approve (Evans et al 2021).

Nor is social pressure always a bad thing. On the contrary.

It can be a helpful trait — perhaps even an essential one — for a species that depends on transmitting cultural ideas to survive. After all, when a behavior becomes popular or widespread, it’s often because that behavior is beneficial or advantageous in some way.

So social pressure can motivate us to adopt to successful strategies. Indeed, adults can use social pressure to encourage kids to behave in ways that are culturally-rewarded. In one study, preschoolers were more likely to delay gratification when researchers led them to believe that their peers were doing the same (Doebel and Munakata 2018).

And of course social pressure can be an important mechanism for fostering prosocial behavior and morality. It can promote sharing, generosity, cooperation, and fairness (e.g., Chai et al 2024; House 2018).

Moreover, children possess the capacity to doubt — and even reject — majority opinion

Studies tell us that kids can resist social pressure. They can question dogma, resist groupthink, and decide — at least sometimes — it’s good to push back.

For instance, in an experiment on 150 preschoolers, researchers found that the presence of a single dissenter — someone who voiced the truth in opposition to the majority — was enough to weaken their conformity to the majority opinion (Enesco et al 2016).

And a variety of experiments indicate that older preschoolers (aged 4 years and above) weigh the reliability of informants. They are more likely to trust people who have first-hand knowledge of a situation, and who have a track record of honesty (Tong et al 2020).

For example, in one study, 4-year-olds were given a choice of claims about the hidden contents of a box. What was inside? Did they favor the majority view, or did they side with a lone dissenter?

When there was no additional information available, kids sided with the majority. But things went differently if the 4-year-olds knew that the majority opinion was based on an unreliable source (an individual who had confided that she hadn’t looked in the box, and was merely pretending to know).

Under these conditions, kids sided with the opinion of a lone individual whom they had seen peering into the box (Kim and Spelke 2020).

Is this enough to protect kids from making bad choices?

Clearly not. Kids aren’t just susceptible to social pressure. They are also prey to the many cognitive biases, fallacies, and poor thinking habits that plague adults.

But our children are equipped with some of the basic tools needed to make public judgments about the truth. If we want them to show backbone — to stick to the facts even when it’s unpopular — we need to encourage them. To talk about fact-checking and self-reflection, and the difficulties we can face when we choose to go against the flow.

We can teach them when it’s appropriate to speak up. We can give them the support they need to stand their ground. We can be good role models.

And we can do these things with the understanding that we’ve inherited a complex human nature. We can imitate and conform. We can also reason and challenge. We need both modes to create an adaptable, progressive, democratic society.

References: When does peer pressure start?

Chai Q, Yin J, Shen M, amd He J. 2024. Act generously when others do so: Majority influence on young children’s sharing behavior. Developmental science e13472 .

Corriveau K, Kim E, Song G, and Harris P. 2013. Young children’s deference to a majority varies by culture and judgment setting. Culture and Cognition 13: 367–381.

Doebel S. and Munakata Y. 2018. Group Influences on Engaging Self-Control: Children Delay Gratification and Value It More When Their In-Group Delays and Their Out-Group Doesn’t. Psychol Sci. 29(5):738-748.

Enesco I, Sebastián-Enesco C, Guerrero S, Quan S, Garijo S. 2016. What Makes Children Defy Majorities? The Role of Dissenters in Chinese and Spanish Preschoolers’ Social Judgments. Front Psychol. 7:1695.

Evans CL, Burdett ERR, Murray K, and Carpenter M. 2021. When does it pay to follow the crowd? Children optimize imitation of causally irrelevant actions performed by a majority. J Exp Child Psychol. 212:105229

Haun DBM and Tomasello M. 2011. Conformity to Peer Pressure in Preschool Children. Child Development 82(6):1759-67.

House BR. 2018. How do social norms influence prosocial development? Curr Opin Psychol. 20:87-91.

Kim EB, Chen C, Smetana JG, Greenberger E. 2016. Does children’s moral compass waver under social pressure? Using the conformity paradigm to test preschoolers’ moral and social-conventional judgments. J Exp Child Psychol. 150:241-251

Tong Y, Wang F, and Danovitch J. 2020. The role of epistemic and social characteristics in children’s selective trust: Three meta-analyses. Dev Sci. 23(2):e12895.

Image credits for “When does peer pressure start?”

Title of ducks in a row by allanswart / istock

images of bears by Iya Balushkina / shutterstock

image of girl reading by Skolova / shutterstock

image of boy taunting child by Lopolo / shutterstock

Portions of this text appeared in a post for BabyCenter, “Peer pressure in preschool: What kids will do to conform,” written by Gwen Dewar in 2011. In addition, this article has been modified and updated since it’s original publication in 2020.

Content last modified 3/2024